By Tom Kisken

Originally published in the VC Star

The company captain lay sprawled on the ground with wounds that threatened his life.

More than 120 Marines, most of them teenagers, were pinned in a muddy ditch by machine gun fire coming from two directions outside of Hue, Vietnam.

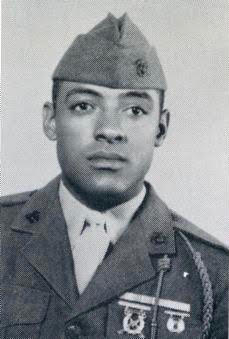

Gunnery Sgt. John Canley, a quiet, tall Marine lifer from Arkansas, took command of the company because the captain was down.

It was his job to keep his men alive and lead them into Hue.

If you want to know what happened, don’t ask Canley, the 80-year-old Oxnard resident who stands on the cusp of being honored with the military’s highest award — the Medal of Honor. U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis approved the award in December, triggering a bill that passed the House and Senate waiving the normal five-year time limit.

President Donald Trump signed the bill Monday and needs to provide a final approval for the medal to complete a drive that began in 2005. It’s unclear when a presentation ceremony would be held.

Canley will appear at a different ceremony Tuesday night, wearing his dress blues for Trump’s State of the Union address at the U.S. Capitol. Retired as a sergeant major after 28 years in the Marines, he and his daughter, Patricia, will be guests of U.S. Rep. Julia Brownley. The Democrat from Westlake Village helped lead a battle of just due that dates back to those bleeding Marines in the ditch on the last day of January 1968.

In an interview before flying to Washington, D.C., Canley said it’s not his place to talk about what he did to earn the medal in and outside of Hue. It’s not the Marine way.

Instead, that duty falls to the men who served with him in that battle.

Pat Fraleigh, then a 19-year-old private from Poughkeepsie, N.Y., was hit by rockets. Streams of blood gushed from his neck, his arms, pretty much everywhere.

One tank back, Canley leaped from his vehicle and ran into the blizzard of enemy fire. He pulled Fraleigh into a thatched hut and tried to patch him up.

When Fraleigh appeared to stop breathing, Canley worried he died and carefully covered him with a poncho. Several hours later, Fraleigh was picked up by a morgue truck that lurched toward a field hospital, his body sandwiched between the tailgate and corpses.

“When the corpsman unlatched the tailgate, I kind of popped up and he said, “Holy s—, he’s alive,'” Fraleigh said. He knows Canley’s actions saved him.

“I probably would have laid there and bled to death,” he said. “He’s a helluva guy, believe me. He’s a Marine’s Marine.”

Herbert Watkins was also there. The 21-year-old Marine nicknamed Buzzard was on one of the trucks and was hit by shrapnel outside Hue. Almost everyone got hit that day, including Canley who was bleeding from the face but ignored the wound.

“He was all over the place. He was charging machine gun nests, him and (Sgt. Alfredo) Gonzalez,” said Watkins in a phone interview from Manchester, N.H., where he retired after 36 years with the Post Office.

“He was directing fire, dragging people out of the street and he was always so calm. … It’s like it happened yesterday. I still visualize everything,” Watkins said, thinking of the sergeant the Marines still call Gunny. “Oh, a great man, a man of stone.”

Canley and Gonzalez fired M16 rockets and charged close enough to lob hand grenades and take out a machine gun site. They opened up a hole that allowed the bloodied battered Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment to advance into Hue and the heart of the Tet Offensive.

It took three days before new officers arrived for Alpha 1/1. John Ligato, a private first class who became an FBI agent after the war, calls them the missing days.

Canley, still in command, performed the way he always did. He stood when others ducked. He ran into enemy fire to rescue his men, sometimes a cigarette still tucked into his mouth.

He encouraged and listened and led.

“He was John Wayne,” Ligato said. “We all like to think we’re a little brave. He’s on a different plane.”

There were two lifers: Canley and Gonzalez who died a few days after the company made it into Hue. Canley led the drive for Gonzalez to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor.

No one was left to write up Canley. The men he led finished their tours and left, coming back to a nation that had grown to hate the war. They lost touch with each other.

“No one wanted to talk about the (war) for 20 to 30 years,” Ligato said.

But historians recognized the importance of the Hue battle. They reached out to Marines to learn exactly what happened. Canley refused to talk but Ligato and others told the story. The legend of Gunny grew.

Reunions brought the company back together. In 2005, Ligato started a drive to upgrade the Navy Cross Canely won — along with a purple heart and two bronze stars — to the Medal of Honor for his acts during the missing days.

He reached out to Marines and collected stories of Canley’s heroism, how he carried wounded men to safety almost routinely.

“I never saw such a Marine as him,” Watkins said. “It was amazing. He’d walk around nice and calm, rounds flying all around him.”

Ligato needed two testimonials. He offered several times more than that.

Still, the drive for the Medal of Honor took 13 years. Ligato said there were bureaucratic hurdles like misplaced papers and the insistence on signatures from a long line of commanding officers.

The problem was that many of the officers were dead.

“I gave up a few times,” said Ligato who always resumed his efforts. “I thought I let him down.”

Ligato came to Brownley’s staff in 2014 and asked the congresswoman to join the drive. In a phone interview, she called Canley’s story incredible.

“The thing that stood out to me the most was that (Canley) always requested to return to Vietnam,” she said. “They tried to give him a desk job. He said no.”

After Mattis approved the Medal of Honor, the House and Senate gave unanimous votes of consent on Brownley’s bill waiving the five-year time limit. The congresswoman’s staff reported hours before Monday night’s deadline that Trump signed the bill.

“This has been one of my biggest honors since I’ve been in Congress,” she said earlier, noting only about 70 Medal of Honor recipients are still living. “This is really, really important.”

In an Oxnard sandwich shop, Canley told stories about arranging for helicopters to deliver 500 pounds of ice so his men could enjoy a cold beer. He still jogs three miles every other day and talked about his excitement at possibly leading the Marines currently in Alpha 1/1 in physical fitness training later this year.

He talked too about the nightmare of war. A half-century later, he still has dreams, still struggles to sleep at night.

In that kind of place, the key to leadership is to spend time with people, Canley said. You have to understand what’s important to them and help them defeat whatever stands in their way.

“How do I feel about them?” he said of his Marines, incredulous at the question. “I love them.”

The feeling dictates how Canley views the Medal of Honor. The country sent his Marines to a war 8,000 miles away from home. When they returned, they faced anger and rejection — as if they had somehow started the war.

“It haunts me every day that these Marines did not receive recognition,” Canley said, noting the Medal of Honor is for them.

“This is not about me,” he said. “This is about the young Marines that sacrificed so much. I just happened to be their leader.”

Issues: 115th Congress, Veterans' Affairs